ニュースサイトから英語学習にうってつけの記事を厳選していく、多読向け教材シリーズ。

久々の登場です。私Fukuoka English Gym代表のOkadaは日々、The New York Times, USA Today, Washington Post, Bloomberg, Newsweek といったニュース系の記事を読むことをルーティン化しています。

今回はアメリカ最大の週刊誌TIMEのウェブサイト版より。

アメリカ最大のニュース雑誌。1923年創刊という超老舗。政治・経済・テクノロジー・エンターテインメント・デイリーニュースなど様々なニュースを扱っている。ウェブサイト版は多くの英語学習者に親しまれており、語彙レベルはWashington PostやThe New York TImesより易しめのため読みやすい。難しいという場合は、子ども向けのTIME for Kidsからスタートするとよいでしょう。Time for Kidsは日本では中堅大学以下の大学入試の問題の出典になっていることが多いです。

Article (記事)

‘A Monsoon on Steroids.’ What To Know About Pakistan’s Catastrophic Floods

https://time.com/6209967/pakistan-floods-what-to-know/

BY SANYA MANSOOR AUGUST 31, 2022 12:58 PM EDT

6月よりモンスーンによって降り続いた雨によって8月末までで歴史的な洪水が起きた。その現状と原因となる真犯人とは。

Number of Words:1200 words

およそ1200語です。

黙読なら6分、音読なら7分30秒で読み切れればスピードリーディングのスキル(=速読力)はかなり高いと言えるでしょう。 [WPM 黙読200 音読160 で算出]

Text: 本文(Source : https://time.com/6209967/pakistan-floods-what-to-know/)

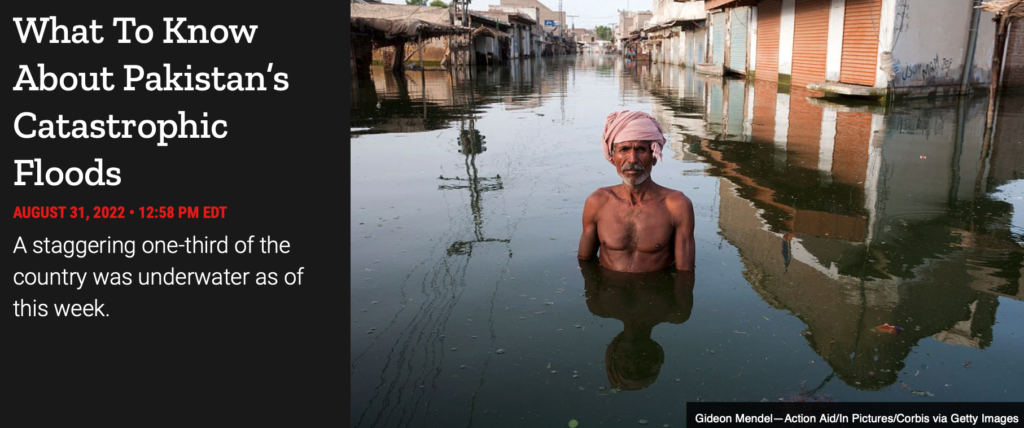

What To Know About Pakistan’s Catastrophic Floods

Pakistan is grappling with its worst flooding in living memory. A staggering one-third of the country was underwater as of this week, with more than 30 million people affected over the last few weeks—killing at least 1,100 civilians and pushing almost half a million people into relief camps. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has referred to the disaster as a “monsoon on steroids” that “requires urgent, collective action.”

The immediate cause of the catastrophic floods is record rainfall. “So far this year the rain is running at more than 780% above average levels,” said Abid Qaiyum Suleri, a director at Pakistan’s Sustainable Development Policy Institute. Melting glaciers—Pakistan has more glaciers than any other country—is also contributing to the floods, which are linked to climate change.

It was only in 2010 when Pakistan last experienced such extensive floods but officials have already suggested that the damage from this year’s calamity is worse. That year, then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon had described them as the worst natural disaster he had ever seen—not just in Pakistan but anywhere in the world. The 2010 floods affected about 20 million people and led to more than 1,500 deaths.

The U.N. said Tuesday that it is seeking $160 million in emergency aid for the ongoing floods, noting that nearly 1 million homes had been damaged and more than 700,000 livestock were lost. The U.S. announced that same day it would send $30 million in aid to Pakistan. Humanitarian relief has started to arrive in the country, but efforts have been hampered by extensive infrastructural damage; over 2,000 miles of roads and 150 bridges have been affected.

Nauroz Jamali, a social sciences lecturer at LUAWMS University in Balochistan, has been helping with the volunteer effort in the southwestern province’s villages, including Gandakha. “This whole town has been converted into a dam with multiple sources of water pouring in but with no exit so it’s killing people feet by feet; it chokes us,” he says. Jamali adds that the floods had trapped his uncle, whom he helped eventually evacuate. “We are helping so many people with little manpower and we are in such a confused state. We don’t know what to do.”

Building climate resilience

Experts say Pakistan has not done enough to prepare for floods, which are frequent in the country. Countries with similar risk profiles such as Nepal and Vietnam have invested in building infrastructure to absorb climate shocks, says Amiera Sawas, director of programs and research at Climate Outreach and a climate and water expert on Pakistan. “There’s just nothing in Pakistan [in terms of disaster resilient infrastructure]—so people were literally left to fend for themselves against really extreme weather, which we knew was going to come at some point.”

Pakistan has recently focused on mega-projects such as building dams to manage water, but this has worsened the effects of flooding. The pockets of water caused by dams overflow during extreme rain.

Balochistan, the worst affected and an economically under-developed province, has not been a priority for the Pakistani government during the floods, Jamali says. “The government is not serious. They don’t understand this idea of climate change.”

Meanwhile, the floods have hit Pakistan in the midst of a political and economic crisis. Earlier this year, former Prime Minister Khan was replaced with Shehbaz Sharif after being removed through a parliamentary vote of no confidence in April. Khan has since upped his criticism of the government and police charged him earlier this month under anti-terror legislation after he lambasted them over the arrest and alleged torture of a close aide.

Read More: Why Pakistan’s Plan to Silence Imran Khan May Backfire

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a $1.1 billion bailout packageMonday for Pakistan to help the nation avoid an imminent default. Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the South Asia program at the Wilson Center, points out that Pakistan is already dealing with skyrocketing food prices that will likely increase even more because supplies will go down with entire harvests wiped out. “The economic crisis, food insecurity, it all sort of plays together, and makes for a perfect storm that will really complicate these recovery and reconstruction efforts,” he says.

And recovery will be hampered by a monsoon period that is not yet over. “It’s going to be difficult to focus on recovery if you’ve got more rain,” Kugelman adds.

For her part, Climate Outreach’s Sawas says that climate change is Pakistan’s biggest security risk—and deserves the investment that recognizes it as such. “The idea of security is a very old school militarized notion of Pakistan vs. India. But if we look at the situation now—millions are in distress. That is a massive human security issue,” she says. “There needs to be a real step back and reflection going forward on what’s important and how budgets should be prioritized and I’m just really worried they’ll forget again.”

“The onus is on the international community”

But the floods have also called attention to the global inequity in who bears the brunt of the climate crisis; Pakistan has been responsible for only 0.4% of the world’s historic CO2 emissions. “The onus is on the international community—particularly the industrialized world in the West and countries like China—to do more to help Pakistan, but also Pakistan arguably could have done a better job to keep its backyard in better order in terms of climate proofing and emissions reductions,” says Kugelman.

Maira Hayat, an assistant professor of environment and peace studies at the University of Notre Dame, told the BBC about how Pakistanis may rightly be focused on holding the state accountable but that citizens of the Global North needed to reflect on how their countries have contributed to the climate crisis. “[Pakistanis] know to hold the state accountable. But there are certain other questions that citizens of the Global North need to be asking of their states,” Hayat said. “So for example, what is the responsibility of the Global North in the kind of devastation that we’re seeing in Pakistan today?”

Part of that introspection for rich countries entails a serious conversation about who should pay for “loss and damage” in poorer countries, Hayat and others have said. Many climate activists and politicians are pushing for countries responsible for the most CO2 emissions to be required to foot a larger part of the bill. At the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, signatories recognized the issue but have since stopped short of an enforcement mechanism to put the program into place; the U.S. and E.U. have actively resisted such efforts. Sawas hopes that Pakistan’s floods will call attention to the “loss and damage” issue ahead of the U.N.’s COP 27 meeting in November.

In the meantime, even with donations pouring in, it can still be a challenge to secure supplies—as Jamali’s volunteer efforts show. “We now have donations but we don’t have a market to buy things or don’t have a way to bring things here; in the morning we sent for a tractor to bring rations but are still waiting because the road is blocked,” he says. “I just feel helpless.”

Highlights(キーポイント)

● 強烈なモンスーンの影響でパキスタンで歴史上最悪な洪水が起きた。8月末時点で国土の3分の1が水没している。およそ50万人が避難キャンプへ押し寄せている。モンスーンによる雨量は歴史的なもので通常の780%増。またパキスタンには世界的にみて氷河の量が多い。その氷河が溶けていることも気候変動と関連する洪水の原因となっているだろう。

Pakistan is grappling with its worst flooding in living memory. A staggering one-third of the country was underwater as of this week, with more than 30 million people affected over the last few weeks—killing at least 1,100 civilians and pushing almost half a million people into relief camps. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has referred to the disaster as a “monsoon on steroids” that “requires urgent, collective action.”

The immediate cause of the catastrophic floods is record rainfall. “So far this year the rain is running at more than 780% above average levels,” said Abid Qaiyum Suleri, a director at Pakistan’s Sustainable Development Policy Institute. Melting glaciers—Pakistan has more glaciers than any other country—is also contributing to the floods, which are linked to climate change.

●国連によると、この洪水の緊急援助には16億ドルが必要だ。ほぼ100万世帯が損壊、70万以上の家畜が失われている。アメリカは3000万ドルの支援を発表、人道支援救済も始まっている。しかし、膨大なインフラの損害でそういった努力は駄目になってしまっている。2000マイル以上の道路や150の橋が損壊の影響を受けているからだ。

The U.N. said Tuesday that it is seeking $160 million in emergency aid for the ongoing floods, noting that nearly 1 million homes had been damaged and more than 700,000 livestock were lost.. The U.S. announced that same day it would send $30 million in aid to Pakistan. Humanitarian relief has started to arrive in the country, but efforts have been hampered by extensive infrastructural damage; over 2,000 miles of roads and 150 bridges have been affected.

●パキスタンは、同じリスクを抱えるネパールやベトナムといったインフラ建設に投資し気候変動のダメージを押さえてきた国と比べると、洪水への準備が十分じゃなかった。パキスタンには災害があっても自助できるインフラという点で何も存在していないと言える。

Experts say Pakistan has not done enough to prepare for floods, which are frequent in the country. Countries with similar risk profiles such as Nepal and Vietnam have invested in building infrastructure to absorb climate shocks, says Amiera Sawas, director of programs and research at Climate Outreach and a climate and water expert on Pakistan. “There’s just nothing in Pakistan [in terms of disaster resilient infrastructure]—so people were literally left to fend for themselves against really extreme weather, which we knew was going to come at some point.”

●気候変動危機の批判の矛先となるのは誰か。洪水によって世界的な不平等に注目が集まっている。パキスタンはCO2排出量が世界的には0.4%のみだ。したがって、この責任は国際社会にある。特に欧米の産業国家、中国のような国々(はCO2排出量が多く気候変動の原因となっている)。そういった国がパキスタンの援助に積極的になるべきだ。パキスタンは気候耐性や排出量の削減という点では優れているのだから。

But the floods have also called attention to the global inequity in who bears the brunt of the climate crisis; Pakistan has been responsible for only 0.4% of the world’s historic CO2 emissions. “The onus is on the international community—particularly the industrialized world in the West and countries like China—to do more to help Pakistan, but also Pakistan arguably could have done a better job to keep its backyard in better order in terms of climate proofing and emissions reductions,” says Kugelman.

Vocab. (語彙)

ニュースに頻繁に登場する hamper

様々なニュースサイトの記事を読んでいて、"hamper"の登場頻度が高いことに気付いている英語学習者の方は結構多いのではないでしょうか。

hamper: hinder / impede the movement or progress of something

hamper 「〜を妨げる」

And recovery will be hampered by a monsoon period that is not yet over. “It’s going to be difficult to focus on recovery if you’ve got more rain,” Kugelman adds.

「それに復旧はまだ終わっていないモンスーン期のせいで止まってしまうだろう。『もしもっと雨が降ったら復旧に集中するのは難しくなるでしょうね』とKugelmanは付け加えている。」

Opinion(私の意見)

まず、この素材なら普通に早稲田大・商などのレベルの大学入試問題にも採用されるくらいの難易度ですので、高校生でも読める内容だと思いました。

さて、8月末に6月から続く雨の影響による洪水で、パキスタンの国土の3分の1が沈みました。主要輸出産業である綿花も、全国で半分近くがだめになった言われています。

ネパールやベトナムのようにインフラ整備に投資をしなかったパキスタンが悪い、という意見もありますが、通常の780%増しの降雨という異常気象の原因は誰でしょうか。気候変動と直結する温室効果ガス、特にCO2の排出量は世界的に見ても極小です。一方、中国など一部の国々はCO2の排出量を抑えきれていません。本記事のように今回のパキスタンの大洪水の主原因は、私たち日本を含めて、世界です。

カフェでストローやふたなどプラスチック製品を受け取らない、コンビニはエコバックを持参する、持続可能な素材の商品を買う...。1人ひとりのちょっとした意識とほんの少しのエコフレンドリーな行動の集合体が、大きな力になる。それが気候変動や異常気象の発生を遅らせられる。今回のような大洪水も防げたかもしれない。

今回この記事を通じて、自分のエコな態度やアクションをあらためて見直してみようと思いました。

そして、類似するどの記事を読んでも、経済的支援が重要と分析されているので、お金の支援の輪を自分の周りで広げていきます。

Video:BBC News

最後にBBC Newsのニュースビデオです。